Central Banks

Central banks regulate national banking systems to protect depositors. They also decide interest rates with the goal of keeping inflation and unemployment rates low.

The Fed

The Federal Reserve is the US’ central banking system. The Fed is run by a board of 14 governors, half of which are appointed by the President and the rest from the private sector. The Chair of the Fed is one of the sitting Governors. Decisions are made by the Fed without congressional approval.

The Fed is comprised of 12 Federal Reserve Banks, separated by region. The Function of the Fed is to:

- conduct monetary policy

- promote stability of the financial system

- provide banking services to commercial banks and depository institutions as well as the govt.

Bank Regulation

Banks are regulated to ensure that they remain solvent by avoiding unnecessary risk. Regulations can come in the form of reserve and capital requirements as well as restrictions on the types of investments.

Supervision

The largest banks in the US are monitored by the Officer of the Comptroller of Currency which is part of the Department of the Treasury.

Credit unions are supervised by the National Credit Union Administration.

The Federal Reserve supervises holding companies that own banks.

Deposit Insurance

To avoid protect depositors against insolvent banks, deposit insurance programs pay out deposit should a member institution fail. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) insures banks in the US, charging banks premiums that depended on the level of risk.

The FDIC reviews the balance sheets of banks to ensure that they remain viable. The Silicon Valley Bank was seized after Fed and FDIC examiners determined that they lacked liquidity and solvency.

Lender of Last Resort

Central banks act as lenders of last resort when many financial institutions fail and banks are unable to secure funds. This reassures deposit insurance.

Executing Monetary Policy

Monetary policy is most applicable during times where banks keep limited reserves. In the current economy, American banks keep ample reserves.

Open Market Operations

Open market operations is a monetary policy tool decided by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The Fed buys or sells Treasuries to influence reserves and interest rates to meet the federal funds rate (FFR), which is the overnight rate between commercial banks.

In open market operations, central banks can pull money out of thin air to buy bonds from banks. When the central bank purchases bonds, money enters the economy, increasing the money supply and vice versa.

The Discount Rate

The discount rate is the rate at which the Fed offers short-term loans to banks. By raising the discount rate, banks are incentivized to borrow less of their reserves from the Fed and take on loans. By reducing the supply of loans, the interest rate goes up and money supply goes down.

The discount rate is higher than the federal funds rate, encouraging banks to get their reserves elsewhere.

Reserve Requirements

Changing the reserve requirement changes how much banks have to lend out.

Ample Reserves

Interest rate on balance (IROB) is the rate paid by the Fed on excess reserves, controlled by the FOMC. By adjusting the IROB, the Fed can target the FFR. Decreasing the IROB incentivizes banks to instead lend at the FFR, creating excess supply, lowering the FFR.

The FOMC lowers the IROB in conjunction with the discount rate. Banks engaging in arbitrage by borrowing at the lower discount rate and lending at the FFR ensure that greater supply lowers rates.

Quantitative Easing

Quantitative easing (QE) is the Fed’s strategy of purchasing long term Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

By purchasing long-term Treasuries, QE lowers long term rates when short term rates are already low. By purchasing MBS, the balance sheets of banks is strengthened from the removal from the undesirable assets.

Quantitative easing is seen as an emergency measure, only temporarily put in place.

Economic Outcomes

Policy that encourages borrowing and lowers interest rates is expansionary/loose. Policy that discourages borrowing and raises rates is contractionary/tight.

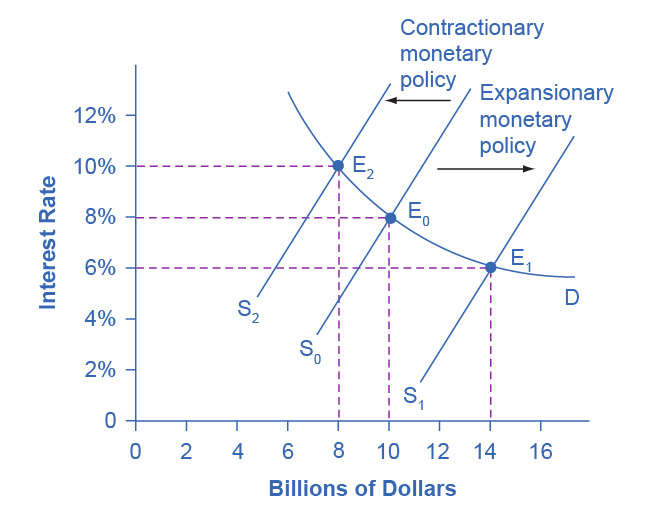

Interest Rates

|

|---|

| Interest rates can be modelled as supply and demand |

The supply curve represents funds that are available for loans. When the FFR changes, the interest rates of other loans will also change. However, the amount of change will depend on the risk and term of such loans.

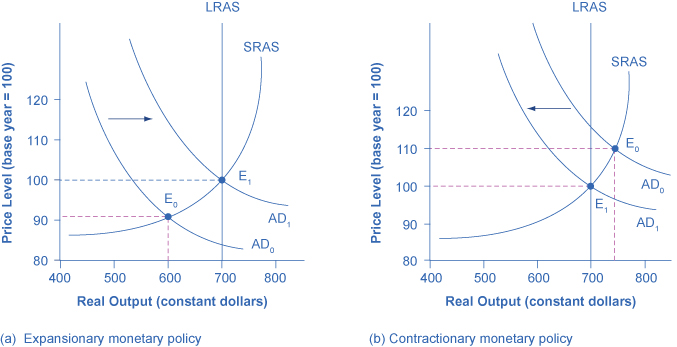

Aggregate Demand

|

|---|

| Changes in AD are represented by a Keynesian SRAS curve |

Monetary policy affecting interest rates can encourage or discourage business investment and consumer borrowing, causing shifts in aggregate demand.

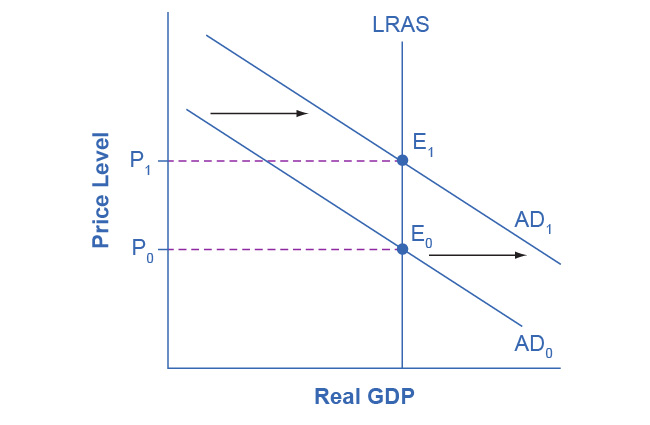

|

|---|

| Countercyclical monetary policy suggests that policy acts to counter movements in the economy due to the [[AP Macroeconomics/Chapter 6#^dd3fcd |

Monetary Policy Pitfalls

Excess Reserves

During recessions, banks cannot be forced to loan out their money and businesses and consumers may not want to borrow. Expansionary policy will thus have little effect.

Velocity

The Velocity of Money

Velocity refers to the speed at which money circulates, defined as:

Recall the definition of nominal GDP:

Therefore,

This is called the basic quantity equation of money. According to this equation, real GDP would increase with the money supply when velocity remains constant. However, when velocity is unpredictable, so is real GDP.

With the advent of electronic banking, M1 velocity has increasingly fluctuated. M2 is a more stable and predictable measure.

Unemployment and Inflation

|

|---|

| Expansionary policy in the neoclassical model |

If the goal of monetary policy is to keep inflation low, expansionary policy only serves to increase inflation in the long run without affecting unemployment or real GDP.

Central banks that are inflation targeting are tasked with keeping rates low, which incentivizes loose monetary policy. Unfortunately, such policies in the neoclassical model would only increase AD, raising the price level without reducing unemployment.

Bubbles

During periods of prosperity, banks are ready to lend and borrow, boosting the money supply according to the money multiplier. This can cause a leverage cycle, where borrowed money boosts an asset class’ price at unsustainable rates. If lending reduces or credit becomes too expensive, the bubble could pop.